New life cycle

By Cheng Anqi (Chinadaily)

Updated: 2008-05-31 07:578 K f% z/ C+ X8 V

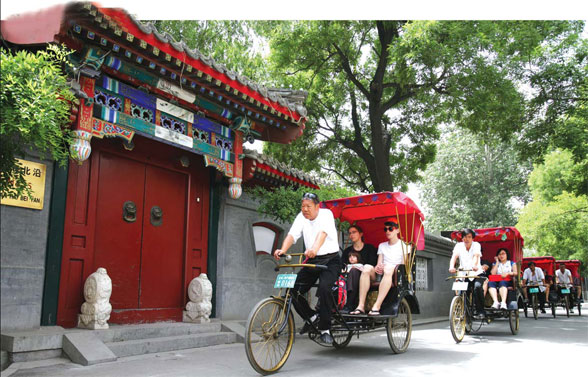

Dawn breaks and Ying Huiqi beats off the dust that has collected on the vehicle overnight, tests the bell on the copper handlebar, folds up the awning and gets ready to receive his first customer of the day. Clad in a white T-shirt and black bloomers, with a pair of traditional fabric shoes and a towel hung at the waist ready for wiping his perspiration, Ying is in his element. "Watch your step," he says cheerfully. "Sit back. Now off we go." He sets out for innermost Beijing, into its hutongs, or quintessential alleyways. The Beijinger has been riding his trishaw for 11 years in the Shichahai area, northwest of the Imperial Palace. Spring and summer are busy tourist seasons, so Ying pedals more than 10 customers every day. The sun has burned his skin, with his neck as tanned and rough as an old peasant toiling the fields year round. He is 58, but Ying professes to have "inexhaustible strength". Ying believes he offers a reflection of Beijing culture and civilian life in these modern times. He often recites to foreigners the story of Camel Xiangzi or Luotuo Xiangzi, the Lao She masterpiece of the tragic life of a rickshaw puller in Beijing of the 1920s. Like many, Ying believes that Xiangzi best represents the era of old Beijing. Xiangzi was a modest rickshaw puller in the capital, but one who dreamed of a rickshaw to call his own. Through Xiangzi's eyes, the old Beijing of just a few decades ago was shown to readers, such as the Bell and Drum towers, the White Dagoda, the pailou or archways, bustling markets and, of course, the life of Beijingers in hutongs. "But what a miserable life Xiangzi had!" Ying says. "Under the scorching sun, in the rain and snow, he waded through all types of difficulties until he succumbed to his failures. On the contrary, I am happy to pull this trishaw." Ying was not always a trishaw rider. After graduating from college in 1966, he got caught up in the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and was assigned to an electrical plant in Qinghai province. With his proficiency in welding, Ying became the backbone of the factory and was invited to join the Association of Qinghai Welding and helped to revive a collapsing private welding plant. But Ying considered time and again to return to the capital. "It was like a calling only in Beijing was I able to feel at home," he says.

Once back in Beijing, Ying did not find it as smooth sailing as he had hoped. He hauled goods and peddled products before finally ending up with the Liuyin Street cultural tourism company. For Ying, the rickshaw - a two-wheeled, manually pulled predecessor of the trishaw - has evolved from a low-status profession to a Beijing experience that comes with a voice narrating civilian life in the capital. "I cannot act as an outsider but instead I make customers feel that I am also a character from these tales," he says. Ying recalls a 70-year-old Briton he brought around. The Beijinger took special care of the visitor, repeating patiently words he could not hear and helping him take photos at every scenic spot. "It was the professional thing to do," Ying says. "But of course, I also hoped for a tip." Ying was disheartened when the senior left without tipping him. But moments later, a 30-year-old man went up to Ying, shook his hand and gave him $20. "That was his son." Not bad for a trip that lasted about three hours and cost 180 yuan ($26) a person. Ying tours vegetable markets, with bustling crowds that inevitably attract curious tourists. He slows down so guests can soak in the atmosphere. "Some foreigners are aware of hutongs located south of the Imperial Palace, and of how people live in the siheyuan or courtyard houses, but that is not all there is to it. "It is the details of everyday life that form its essence." The trishaw is not simply for sightseeing, Ying says. It can also be a conduit for cultural exchange. Ying is well acquainted with hutongs, knowing the details of their construction, layout and building conventions. He knows where the longest, shortest, most twisting and narrow ones are. The siheyuan that make up the hutongs, he is familiar with them, too. Of how their entrances all face south, of the northern rooms reserved for the senior family members and the western and eastern ones set aside for the children of the family. He points out the area where guava trees are grown and how the red color of the fruit depict the desire for numerous offspring. When pulling a large number of tourists, trishaw riders can sometimes by seen traveling side by side under the shade of willow trees. Ying is usually at the head of the convoy in such situations, managing the speed and safety of the group. Two years ago, an overly enthusiastic member was unwilling to keep pace and tried to overtake others. The rogue turned aggressive when fellow pullers complained. Ying reined him in. "Everyone is equal here," Ying said at that time. "If you lay a finger on anyone, I'll beat you and make sure you don't pull anyone for three days." His words proved effective and he did not have to resort to using his fists, something he tries to avoid as much as possible. Ying's optimism is his driving force. Bad weather is no barrier to his work. Prop up his trishaw's canopy, and guests are ready to go. "They can experience the charm of Shichahai in the rain," he beams. As twilight sets in Ying is ready to wind down after a hard day's work. Parking his trishaw together with others at the back of the company building, Ying joins his colleagues for an after-work drink in one of the nearby restaurants. The neon lights of the tourist area gradually turn on, and their reflections dance on the lake in front. Ying feels the cool breeze drying the perspiration on his clothes, and all is well.  |